‘ “Detective stories contain a dream of justice. they project a vision of a world in which wrongs are righted, and villains are betrayed by clues that they did not know they were leaving. A world in which murderers are caught and hanged, and innocent victims are avenged, and future murder is deterred.”

“But it is just a vision, Peter. The world we live in is not like that.” ‘

Thrones, Dominations, Dorothy L. Sayers and Jill Paton Walsh, 1998.

The fictions we love

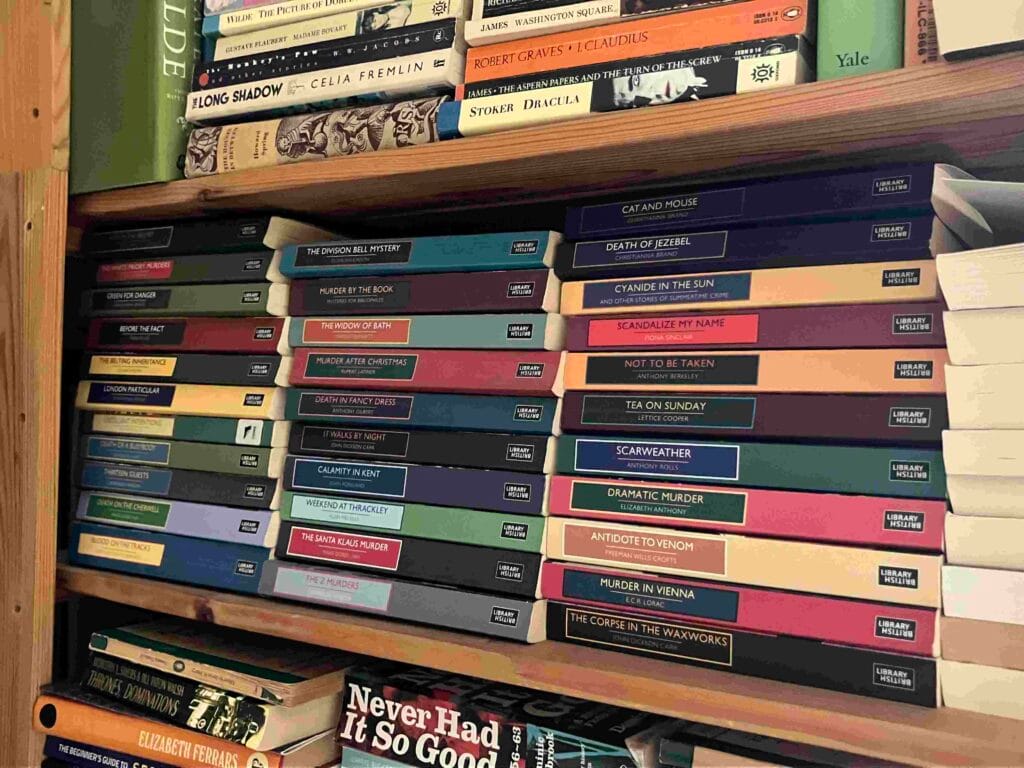

I love British Library Crime Classics and classic crime fiction in general. Despite being a great self-analyser by nature, I still don’t know why I like detective stories so much. In which case I’m even less clear as to why murder mysteries as a genre are so wildly popular. I can feel the pull, but I don’t understand it. Cosy mysteries are one of the biggest genres in fiction at the moment. Have a think about that: cosy murders, killings with no ‘unpleasantness’. How does that make any sense?

Making Sense

It doesn’t, of course. And that brings me to one of the myths of classic crime fiction, and a good deal of other crime fiction, that is part of its appeal. It creates a world that makes sense. Or at least one that you can work out if you have sufficient information. The stories take place within a world where people behave logically even if it’s in consequence of irrational feelings.

If you happen to be interested in true crime as well as crime fiction, then I’m sure that you realise that this is nonsense. People are not rational. In my experience, many of them struggle to be logical unless they have been taught. (Sadly, the English school mathematics syllabus doesn’t seem to find logic important, even if it is one of the most useful skills that mathematics can teach the average non-mathematical person.)

Famous Crimes

During the classic crime era, authors and readers were so in thrall to the idea that people were rational, that there were quite a few attempts made by authors to deduce the ‘true’ solutions of famous crimes. Penguin published very popular accounts of famous trials. Perusal of these will soon convince you, I hope, that people do not behave rationally.

If you find reasons why one protagonist’s behaviour would be logical then you render the others’ nonsensical. Often there is no solution where everyone behaves comprehensibly.

A more modern example that springs to mind is the notorious White House Farm case. Nothing in that story makes any sense at all, not least the actions of the police.

Justice or something else?

I don’t think most people are looking for myths of justice as Lord Peter Wimsey says. At least not nowadays. But I do think they feel comforted by a world in which everything is explicable if we can find enough information. An existence that is always comprehensible if we only look hard enough.

Classic crime fiction, where the solution is almost always revealed, gives satisfying closure. And that’s a myth, because life is not always so tidy.

A Fairy Story

Interestingly, there is one subject in which the assumptions of rationality and perfect information are taken as a given, indeed as a basis for modelling. And that is economics. I’m not suggesting that modern economics was influenced by detective fiction, but perhaps they both grew out of an intense belief in rationality that was fashionable in the early twentieth century. The abhorrence of eugenics became popular about then too.

These are quite important assumptions, because most of the world’s economies are run according to models that rely on them. And look where we are. A mathematical model can only give a meaningful result if it is based on valid assumptions, and most of human society is run on the basis of a system that assumes the complete nonsense that people are perfectly rational and perfectly informed.

The people who follow these models generally believe that money, a human construct with no physical reality, is always in limited supply, but that the resources of our finite planet are capable of supporting infinite growth. Ironically, a perfect example of human irrationality.

Immunise Yourself Against AI

We Are Not Robots

Humans are certainly capable of sound logic, and it is a valuable skill that should feature more in our education. But we are not governed by it. And the premises for our logic often come from feelings, memories, associations or even biological triggers. They are not necessarily rational.

For example, if I now feel like eating a banana I would, quite logically, find the nearest banana and eat it. That might not be rational though. I might have just had a meal and not really need any more food. The nearest banana might be in Tesco and if I eat it without paying for it, there may be unpleasant consequences. And – to borrow from the madness of economic theory – even if I do travel to Tesco for the banana and pay for it before I eat it, that may well be a less than optimal use of my time and resources.

Anyway, even with my limited technical knowledge, I can guarantee that there is currently not a single AI bot on the planet that is currently feeling like eating a banana. We are not robots, so why limit ourselves by the comparison?

Discursive Thinking

It may be lack of confidence in their own logic and memory skills that leads so many to be in thrall to AI. (You can read an article by me about our official AI policy on the Castle Sefton Press site). But lots of us don’t like it and don’t want it. What can we do?

The answer is to abandon the worship of logic and rationality and embrace all the human traits that robots don’t have. Let’s take AI as a challenge to break out of our settled moulds and explore just what we can feel, taste, desire, imagine, love and more.

We can also embrace a kind of logic process that is not robot friendly that I shall call ‘discursive thinking’. Part of the definition of discursive in my Shorter Oxford Dictionary is as follows:

- […] ; rambling, digressive; extending over or dealing with a wide range of topics.

- Proceeding by argument or reasoning; […] .

Let’s combine the two for thinking that rambles over a wide range of digressive topics with perfect logic. Bots struggle with that. They don’t like digression. I know this because it’s naturally the way I write, and I also know how difficult my articles are to optimise for search engines! I don’t think bots understand the link between Tinned Salmon and the Totality of Life for example.

Overheating

Perhaps if enough of us try to be wildly human and very unrobotic we will cause enough bot confusion to melt a few data centres. Just a thought.

The great detective

Back in classic detective fiction, there is a very famous detective whose thinking is of the discursive kind that I have just described. Who consistently runs rings round the best of Scotland Yard by letting her mind ramble over a wide range of trvial topics with faultless logic? Miss Marple of course! Like Kitty Packard in Dinner at Eight (though for very different reasons), she could never be replaced by AI.

The British Police in Detective Fiction

I’ve mentioned before that there tends to be a subject that naturally forces itself on my intention and this month that has been the police. The police are always in the news of course, and they are almost always in crime fiction. In addition we visited the excellent Cheshire Museum of Policing and I came across a very interesting book about the Metropolitan Police’s relationship with the film industry, The Metropolitan Police and the British Film Industry, 1919-1956 by Alex Rock.

The Police

There have been lots of concerning things in the media about the police recently. From institutional racism and misogyny in the Met, to the arrest of pensioners holding pieces of cardboard and the lack of availability of officers to attend fairly serious crimes. These are all things that we should be concerned about, but they are not new things.

In Clive Emsley’s well-researched and entertaining book The Great British Bobby, we find that from the earliest days the British police were a mixture of the corrupt, drunk and violent and the committed and competent. There were some good detectives as early as the Bow Street days. But officers were always constrained by their superiors, the government and the laws they were employed to defend. And there were always problems finding enough good recruits.

It’s always been a difficult and dangerous job too, as well as being underpaid, underfunded and understaffed. And there has always been a good deal of public hostility towards the force. An interesting article about the current situation from police officer Alfie Moore suggests little has changed in these regards.

The Establishment

It’s only to be expected that a body created and designed to defend and support the established laws and government of our country should defend and support the establishment. By which I mean the established power structure of our society. And sadly, in the context of history, it’s no surprise that an establishment-supporting institution harbours racists and misogynists. But there should have been much more progress here.

In an organisation that constantly deals with the violent and faces violence against itself, you can expect that that will provoke violent reactions in some. And any social structure based on power over others will always attract some bullies. At one time school teaching was the same.

The bottom line is, the police do a difficult, demanding and very necessary job. If we don’t like things that they do in defence of the establishment, or the culture of the force, then we should be looking to get ourselves a better establishment for them to serve with a better culture for them to be part of.

The Perfect Policeman

So if the current issues around the police are not new, why are we so shocked by them? Could it be because the English have a preconceived idea of what our police are like? Would that preconceived idea be of someone fair, committed, respectable and tough but unarmed who justly defends the good laws of a free country? Someone like Jack Hawkins’ characters in the excellent 50s films The Long Arm and Gideon’s Day, perhaps.

Have we have forgotten all those unpleasant wide-boy cops in The Sweeney and other 70s shows as quickly as we did the post-war consensus? Or did we just never really believe in either of them?

Ted Willis and the Craft of Screenwriting

Dixon of Dock Green

If you’re younger than me you may not know who George Dixon is. But for anyone who remembers the 1960s, he probably springs to mind as the perfect British police officer. PC Dixon was a fictional policeman played by Jack Warner the 1950 film The Blue Lamp who was then given his own BBC TV series which ran from 1955 to 1976. The character became something of an institution, known as the idealised beat policeman who knew all the locals, was always ready to help and was above reproach himself. It has since come to be regarded as a ridiculously cosy portrayal of police work. Another myth of crime fiction.

In Alex Rock’s fascinating book (mentioned above), I discovered that The Blue Lamp was made under the control of the Metropolitan Police to portray the image they wanted for the force. This was both to improve the public’s relations with the police, which were deteriorating after the war, and to improve recruitment.

Nevertheless, on the limited evidence available – very few of the 50s and 60s episodes survive – I think the television series was initially more than comforting propaganda.

Not So Cosy

The TV series was created and written by Ted Willis as a character-based drama about the working life of an ordinary policeman. Willis was an extraordinarily prolific writer of film, television and novels. His early work in the 1950s was ‘kitchen sink’ drama – i.e. about British working-class life. To me it’s far more convincing than the ‘New Wave’ and other much lauded writing of the late 50s and early 60s. I particularly like his film Woman in a Dressing Gown, which is well worth watching next time it comes round on Talking Pictures TV.

The early series of Dixon are not particularly cosy. There are police corruption and guns and Dixon is not infallible. Most of the characters are neither good nor bad but a mixture of the two, and life is hard for everyone. By the 60s, the series does seem to have become the more comfortable, predictable one that people remember. But if you can consider the early episodes in isolation, they are quality social drama. The change seems to have been at about the time that Ted Willis stopped writing the scripts and others took over.

Prolific Screenwriting

I’ve always had a fascination and respect for the craft of writing. In earlier times, British television screenwriters often had to come up with stories under pressure. Their scripts had to work with a very restricted budget and complicated technical considerations. What a skill to be able to keep delivering the goods under those circumstances!

I recently saw an interview with Brian Clemens, another prolific screenwriter. He described how working for budget film and television producers in his early days had honed his skills. After being forced to come up with stories for unlikely combinations of leftover sets, or for films that could be cut to different lengths for different markets, he felt he could tackle any script problem that arose in his later career.

I do love literature, but I also love to be entertained. I’m not ashamed to be inspired and influenced by retro British film and television. Those people were living on their wits and they often did a good job, and occasionally a great one.

The Fictional Policeman

I suspect that crime fiction – in books, films and television – gives most people their idea of our police force. The cosy Dixon that emerged in the mid 60s became a comforting reality to some and a ridiculous anachronism to others who believed in a more critical version of the constabulary.

A Consciously Created Image

Alex Rock shows how, in film, that was for many years an entirely fictional portrayal. This was because the police refused any cooperation or involvement with the film industry. After 1945, when the Metropolitan Police became involved in the industry, many details became accurate but far from all because the Met were so keen to control the force’s image.

They went on to be equally influential over The Long Arm, which portrayed an idealised CID.

The image they sought to portray was well-established in the minds of those in charge. In Clive Emsley’s book, he shows how the English police force was consciously developed along different lines to the more militarised French model. There was a determination to keep officers unarmed, on the beat and focussed on crime prevention.

But the British government was in favour of the militarised model for colonial police. And they were still willing to call the army out against British subjects if necessary.

This is a clear example of how the English ruling classes, needing to co-opt the lower classes into their social structures, and make real their own ideas about themselves, used ideas of English superiority and difference. (And that’s something that’s very relevant to the current violence and threat of fascism in our country. But that’s another article …)

Crime Fiction Books

I think that the idea of the perfect British policeman might have been spread and embedded by crime fiction books too. Certainly the majority of authors seemed to have come to round to that view of the police by the mid twentieth century and probably before. So they were ahead of the movies and the official propaganda.

I have no idea why this cultural shift occurred, and if anyone knows of any studies on this subject please let me know in the comments. I am convinced that it was an influential change that affected the reading public’s idea of their police force.

Not very popular

In the early days, the new police were not very popular. Some authors then, such as Charles Dickens, gave them supportive portrayals which did have some influence. But it took a long time for the perfect British policeman to become an established trope.

We can see this in early detective fiction and even in P G Wodehouse. The uniformed policeman is a ridiculous figure of fun, and the professional detective is an idiot. Think of Inspector Lestrade in the Sherlock Holmes stories. Or Poirot’s patsy Inspector Japp in Agatha Christie’s early work. Even Peter Wimsey’s intelligent friend Inspector Parker is isolated among stupid colleagues like Inspector Sugg.

Change of view

Somehow, by the 50s many of us had come to believe in the great British police, Jack Hawkins’ fair, committed, respectable and tough but unarmed copper who justly defends the good laws of a free country. Why and how? Partly, no doubt because the police force had improved a lot over time, had become more professional, more organised and had a clearer concept of its role.

But also, I’m sure, because of some successful attempts at film propaganda. And before that, laying the ground, was a corresponding change in the attitude of detective fiction writers propagated by their enormous popular influence.

Agatha Christie

You can see the change clearly in the progression of Agatha Christie’s work. She starts with the dim-witted but confident Japp but Poirot later works alongside Superintendent Battle and Superintendent Spence, very much of the Jack Hawkins type. And very much the police officers we’d all like to deal with if we ever have to. Miss Marple starts with her foil the blindly robotic Inspector Slack but moves on to the charming and intelligent Inspector Craddock.

The brilliant amateur detective goes from being the saviour of justice and the scourge of the incompetent police, to the inspirational colleague and confident of the dedicated professional officer. Partly this must have been for practical reasons, as the development of the force and the scientific side of detection soon rendered amateurs working alone incredible. Perhaps it was even a sign of renewed patriotism and a desire to distinguish ourselves from the increasingly militarised Europe of the 30s.

Whatever the reason, the adoption of this attitude by writers reinforced it and cemented it by embodying it in likeable and admirable characters who were actors in addictive and memorable stories.

Police officers could now be heroes.

The Myths of Classic Crime Fiction

So what does classic crime fiction and its myths offer us? And has it a good or harmful influence?

Satisfaction

Well, like all myths and fiction, they can’t do too much harm if we remember they are not real. They do not portray the world and life as they are. They give us the satisfaction of a puzzle solved, and a closed story, which is perfectly acceptable form of escapism. (Jane Austen uses the same technique). As long as we don’t get lost in the fantasy and become disillusioned that reality does not correspond.

Harmful Influence

They portray human behaviour as more logical and rational than it truly is. In fact, other fiction often does that too to make a story ‘make sense’. This could have the positive effect of encouraging readers to learn to be more logical, but in practice I think it merely reinforces a false idea of humanity, its motivations and its behaviour. That makes the nonsense of the systems by which we are ruled seem more acceptable. As they cause great suffering and will eventually lead to our destruction, this cannot be a good thing.

The Police

They give us an idealised vision of our police force that is not born out by the messy reality. I am not in favour of propaganda. We need to know the true state of our police force, so that we can act to improve and support it as necessary. And any police force can only be as good as the laws it enforces and the culture it upholds.

But if we have an ideal of our police to move towards – as long as we remember that it is not, and never was the truth – the perfect policeman of detective fiction is a very good one to have. Incorruptible, unarmed when possible, fair, unmoved by class, wealth or influence, keen to help and embedded in the community. Even if that image was created for less than honourable motives, we can be proud to ever have adopted it as what we expect.

Coming Soon

I’m hoping to publish next month’s article earlier in the month to get a little ahead before Christmas. So more will be on the way very soon!

Subscribe to hear about new articles:

Leave a Reply