Writing Style

General Fiction

I call myself an author of literary fiction, but what is that? Back in the days when I worked in a bookshop, we had crime fiction, science fiction and fantasy fiction and general fiction. Although it has fantasy and mystery elements, my work would have sat on the general fiction shelf among the classics, romances, comedies and Booker prize winners. There was an enormous range, and it would have had no problem fitting in.

Fun as it was to browse the general fiction section in a large shop, it wasn’t always easy to find something you wanted to read. People took a chance on a book, and sometimes they were disappointed. But sometimes they chanced on something wonderful that they would never have knowingly chosen.

Categorisation

Life has become increasingly categorised and less human and messy. A lot of this is down to the increased reliance on information technology. Not use – there is no problem as I see it in using technology – but reliance. When we let the technology rule us, our society changes.

Internet shopping meant that books needed more categorisation because you couldn’t pick them up and make your mind up with your personal mix of information and intuition as you could in a shop. Now it is much easier to be sure you are picking a book of a type that you know you like. And it is very, very much harder to experience a wondrously serendipitous finding.

So, yes, there are benefits to categorisation, but like individualisation (of telephones, for example, or television) it can be polarising. And I fear it may breed intolerance. If you are always cushioned from things that are not to your taste, then when life does force something on you that you don’t like it might be a shock to your ego.

What BookTok Thinks

The fact remains that I have to categorise my writing style and eventually I chose ‘literary fiction.’ This was because my work is much more concerned with quality of language and with central ideas than most other categories of fiction that I have encountered recently. The general opinion on BookTok (the book-themed content on TikTok) is that literary fiction is more character-based than other fiction, which is more plot-based.

That’s nonsense. Perhaps it is true of contemporary literary fiction. I don’t read enough of it to be sure, because much of it does not appeal to me. But there is no reason why a book cannot be literary in the sense of using the craft of language to hone expression, and still be plot-driven. A story can be both plot- and character-driven with the two intertwined, and still be literature.

And literature encompasses all those diverse experiments in style and form that were made in the twentieth century, many of which are neither character- nor plot-driven. Some of them are not driven at all.

Telling

The current writing style is to ‘show not tell’. This means that the story is told through dialogue and action rather than narration. When you approach a good fiction editor now, they will always start by leading you into this style. There is a place for it. But it’s not a type of prose that I enjoy reading, which is perhaps why I don’t read much modern fiction. And it’s impossible to write ideas-based fiction in this style unless you intend to be extremely ambiguous.

My favourite style of prose is what I would describe as the mainstream literary style of the earlier twentieth century, enriched by some of those experimental developments I mentioned. I aim to bring that lucid and balanced style of story-telling to contemporary times and subjects.

Rhythm

If you have ever studied singing, or song composition, or foreign languages, you will know that stress is very important in the English language. It has natural rhythm which varies with regional accents. Everyone knows that this is taken into account when composing poetry, but I also think it is important in prose writing style.

You can use it in the poetic way, as a way of extracting more nuance from the language. But you can also use it to help the reader along, to pace development and time dramatic events. If you are writing about ideas or characters as well as a story, having a good rhythm to your prose can carry the reader into your work so that they don’t struggle to get started, and it can support them through any complex passages of explanation or description.

Humour

For me, humour is engrained in life, and thank goodness because how would we get through without it? I never want to laugh at people from a position of superiority. The deified narrrator or creator is, I hope, a writing style that is no longer used. But the contrasts, inconsistencies and misunderstandings of the human condition are highly entertaining, and I only find humour in my characters in the same fashion that I laugh at myself every day. It’s a quirkiness that we all share, and we’re all in on the joke. There are no butts here.

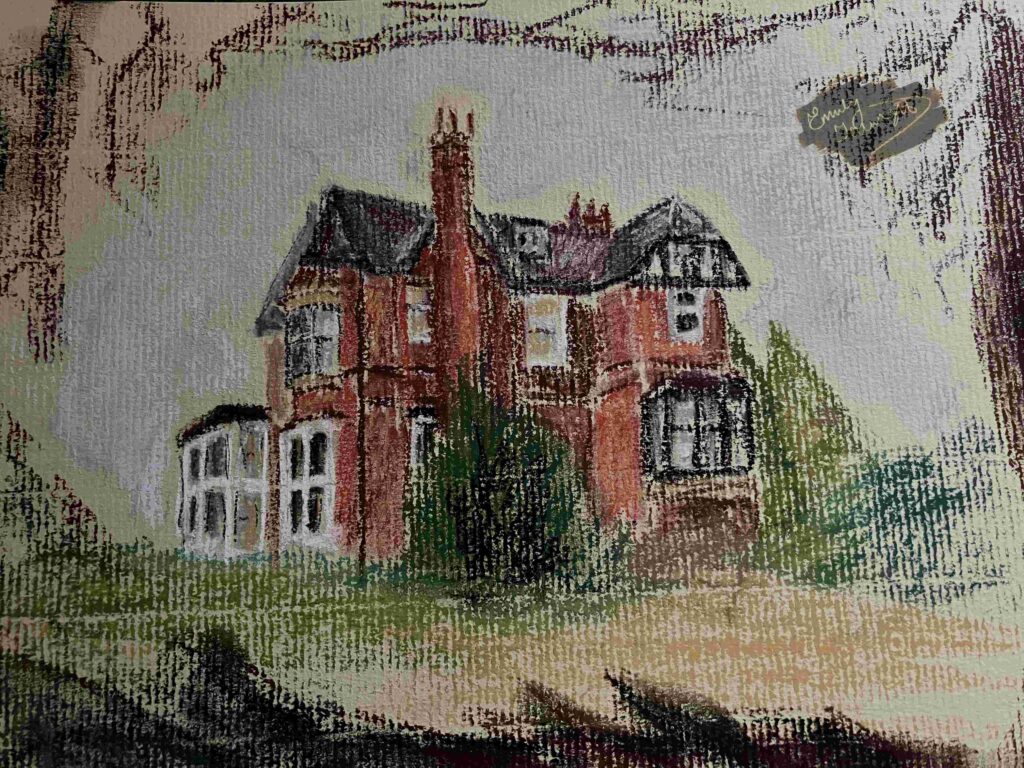

Ghost Train

If you haven’t read my first novel Ghost Train (you can get one from our Castle Sefton Press bookshop), it centres around Clyde Tranter, who together with his wife has bought and renovated a Victorian villa in the Midlands that was previously used as a college. The move triggers changes in their lives and relationship and Clyde begins a journey of personal development that is intertwined with the supernatural happenings that begin in the house. Clyde becomes convinced that the strange events are connected to the murders that once took place there, but is the past always what we think it is?

That’s a question that the book subtly explores as Clyde and his new friends investigate the mystery and build new lives in the process.

Ghost Train

My first novel, Ghost Train, was directly inspired by a local place, The Wedgwood Memorial College in the village of Barlaston, which was once run by Stoke-on-Trent City Council. The main college buildings comprised two large villas that have stood empty and increasingly dilapidated since the college closed.

When I found out that one of Britain’s most brutal twentieth-century murders took place in one of those villas before it became part of the college, the idea for the book came into my mind.

Inspired by my roots

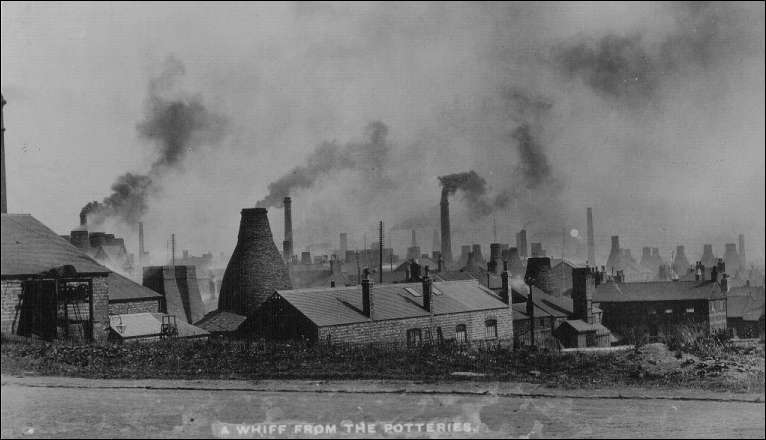

When I started writing Ghost Train I found that the place where I lived was the thing that brought all my ideas together. Stoke-on-Trent – once ‘The Potteries’, being a concentration of ceramic industries – is a unique city in that it is not really a city at all. It comprises six towns that grew until they touched and were eventually incorporated as a city. It is also part of a conurbation with two other towns that did not want to join (and still don’t!).

Despite the efforts of successive local government administrations, and the erection of numerous signs to the contrary, there is no city centre. Strangers seeking this mythical hub will travel round in confusing and infuriating loops to nowhere.

Life here is not quite like that in other cities I have lived in and has much to recommend it, despite the place’s evident poverty and dereliction. It’s an interesting prism through which to view our industrial history and our present society.

Forgotten Stories

Many people leading so-called ordinary lives are not ordinary at all. Some of them are extraordinarily kind, loving, passionate, determined, intelligent or exceptionally good at what they do, even if that is ‘only’ cleaning. I find that this is where the interesting stories are. Not all history is about battles, kings, flouncing about in long frocks and worrying if the new footman is going to be troublesome. If you have a passionate desire, a burning ambition or a desperate challenge, how much more is involved when you have to deal with it while still cooking dinner, cleaning the bathroom and finding money to pay the extortionate water rates.

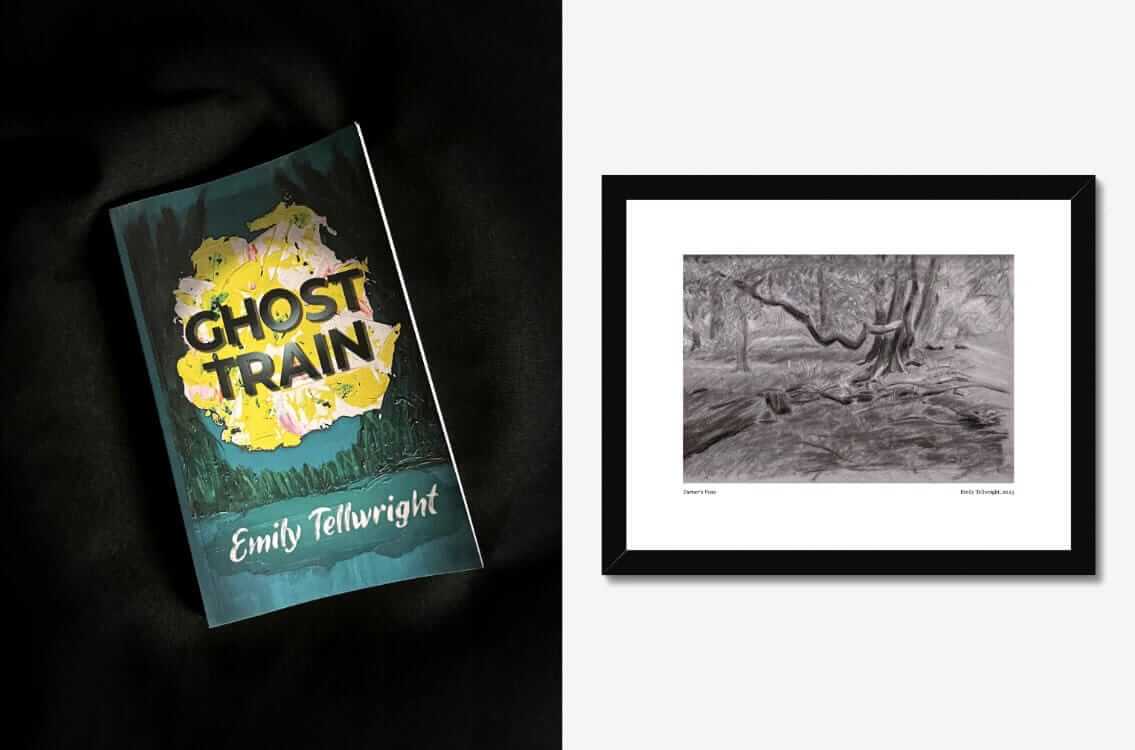

If you’d like to read more of my ideas on life, food, people, books, art, film, television and all the other things that inspire my creative work, have a browse through my blog and sign up to hear when I make a new post. You get my latest artwork too.

Find out more

You can explore Emily Tellwright’s books and art at Castle Sefton Press, and also those of her partner, author and artist John Blake.